California’s Youth Prison System Gets a New Name and a New Home

Commonweal Juvenile Justice Program Program Director David Steinhart was recently featured in San Francisco Chronicle article about proposed legislation to raise the age limit for adult prosecution in California. Read more about David and his juvenile justice work in the following article excerpted from Commonweal News.

***

by David Steinhart Director, Commonweal Juvenile Justice Program

California’s youth prison facilities will no longer be operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation under a reorganization plan launched by Governor Gavin Newsom. Instead, the state’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) will become the Department of Youth and Community Restoration, tucked inside its new home at the Health and Human Services Agency (HHS). The shift was made official in the budget package signed by Newsom in June. It will be fully effective by July 1, 2020.

In his state of the state speech in January, Newsom pledged big reforms of the California juvenile justice system. Uprooting DJJ from the state’s correctional agency is a key first step. The Governor says in his budget summary that the move “… better aligns California’s approach with its rehabilitative mission and core values—providing trauma-informed and developmentally appropriate services in order to support a youth’s return to their community, preventing them from entering the adult system and further enhancing public safety.”

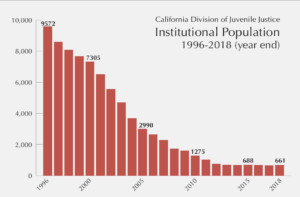

The reorganization of DJJ is yet another milestone in the steady de-escalation and downsizing of the California youth prison system. Back in 1995, the (then-called) California Youth Authority had 10,000 youths locked in a network of 11 large institutions. Ridden with violence, overcrowding, and deplorable conditions, the system was targeted by litigation and law reforms that closed eight institutions and cut the inmate population by 90%. A major link in this chain was the 2007 law (Senate Bill 81) that banned state commitments of youth lacking a serious or violent commitment offense—a law that Commonweal helped to draft and negotiate. Steep drops in youth crime, and rising costs to run DJJ, accelerated the downsizing trend. Today there are just 660 juveniles confined in three remaining youth institutions operated by the state.

The reorganization of DJJ is yet another milestone in the steady de-escalation and downsizing of the California youth prison system. Back in 1995, the (then-called) California Youth Authority had 10,000 youths locked in a network of 11 large institutions. Ridden with violence, overcrowding, and deplorable conditions, the system was targeted by litigation and law reforms that closed eight institutions and cut the inmate population by 90%. A major link in this chain was the 2007 law (Senate Bill 81) that banned state commitments of youth lacking a serious or violent commitment offense—a law that Commonweal helped to draft and negotiate. Steep drops in youth crime, and rising costs to run DJJ, accelerated the downsizing trend. Today there are just 660 juveniles confined in three remaining youth institutions operated by the state.

Youth justice advocates continue to call for the complete shutdown of DJJ. They assert that all juvenile offenders, even those with violent crimes, should be handled in local facilities and programs, closer to the communities to which they must eventually return. But county governments and law enforcement groups have opposed total shutdown, citing public safety concerns and the lack of capacity to house these juvenile offenders in many counties.

New factors are actually increasing demand for state youth corrections space. In 2016, California voters approved Governor Jerry Brown’s Proposition 57 that stopped prosecutors from “direct filing” juvenile cases in adult court. In 2018, lawmakers banned transfers to adult court for most 14-15 year olds. Youth convicted in adult courts go to state prisons for the full adult term. Cutting these adult court pathways means that more youth are instead being sent by courts to DJJ, where incarceration cannot last beyond age 25. With these moves, policymakers and voters have upped the stock of DJJ as an alternative for juveniles that would otherwise go to state prison.

In some sense, then, the Governor’s decision to move DJJ into Health and Human Services represents a middle-ground approach that keeps the system open while responding to advocate calls for change. In fact, the advocacy community wanted a more aggressive reform package from the Governor—including the eventual transfer of the state’s juvenile caseload to county-based care. Instead, the Governor chose the incremental option of reorganizing state youth corrections to Health and Human Services. The reorganization, as embodied in Senate Bill 94, moves the operation but leaves its structure intact. There are no changes in commitment law, ages of confinement, or release decision-making. The state’s aging youth institutions will stay open, with staff moved over from the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. There will be a new advisory committee of advocates and juvenile justice professionals to guide the transformation. But the details of how this will play out—what changes will be made inside the walls, how programs will improve, what re-entry services might expand—remain to be seen.

However it plays out, the shift is a full-circle reminder of reforms that Commonweal called for more than 25 years ago when it published The CYA Report, written by Steve Lerner. He spent time in the institutions and proceeded to document a culture of violence and inhumane conditions. The recommendations in The CYA Report included downsizing the institutions and “humanizing” repressive conditions of confinement. The state has long since downsized the institutions. This latest development—the shift of the remaining operation to Health and Human Services— should take us farther down the road of humanizing what’s left of the state youth corrections system.

Commonweal’s Juvenile Justice Program thanks The California Endowment and the Annie E. Casey Foundation for their generous support. Find out more at comjj.org.